Critics Voice

Rediscovering Korean Cinema — Review by Russell Edwards

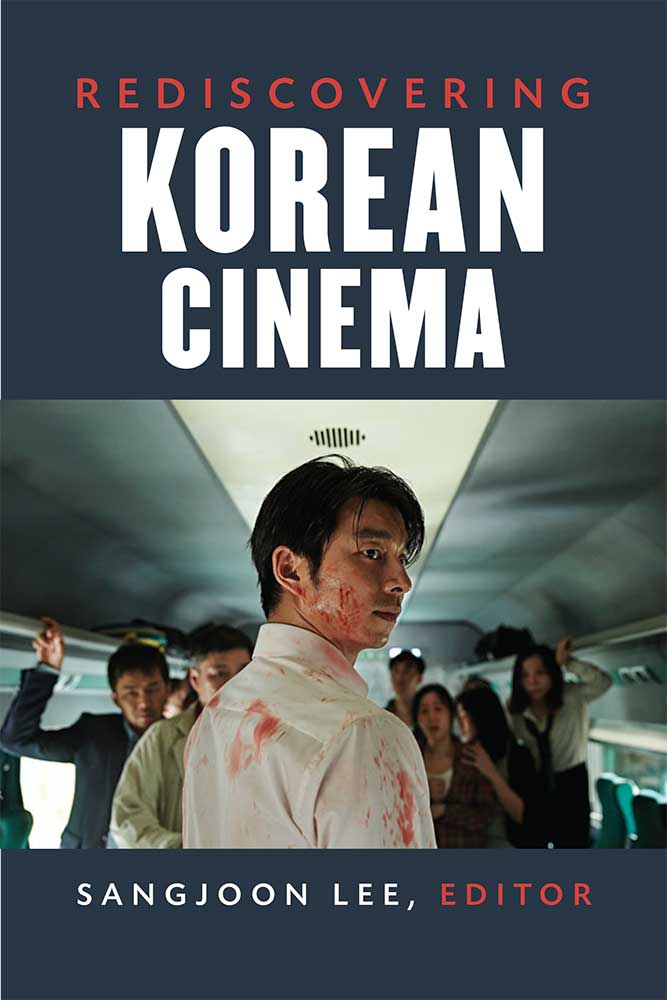

Bitten by the Parasite bug, and want to find out more about Korean cinema? There is probably no more perfectly timed book than this weighty volume, Rediscovering Korean Cinema. Stretching from the beginnings of Korean cinema when the peninsula was still under Japanese occupation to the recent megahits of historical drama Ode to My Father and zombie extravaganza Train to Busan, this series of essays will turn you into a Korean film expert in no time.

The book has a splendid opening chapter by Cho Jun-hyoung which lays out a general history of Korean cinema over thirty pages that presents an overview of the field. But as editor Lee Sang-joon points out in the volume’s introduction, the aim of this book is not to hit you over the head with a history lesson, but to guide the newcomer into Korean cinema one film at a time. Importantly, as Lee also points out, there was no attempt to establish a canon, but to give people insight into films to which they could also have easy access.

This means that the 600-page book splits into roughly two halves: 1) Films up until 1998 and then 2) the films of the new millennium when South Korean cinema really started to hit its stride.

For the first half, the unofficial companion piece to this book is the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube channel which helpfully provides, for free, with English subtitles (and sometimes French, Spanish and Mandarin subtitles), the opportunity to view most of the older films in this volume. So you can read the chapters on landmark films from the 1950s such as Flower in Hell by director Shin Sang-ok (he who was ‘kidnapped’ by North Korea’s Kim Jong-il) and the astounding The Housemaid, Kim Ki-young’s expressionistic thriller that Martin Scorsese once described as “rich and rewarding”, and then click into YouTube straight away. Or (as I would prefer), check the title page for films that sound interesting, watch them on YouTube and then explore an expert’s take on the film straight after.

I’d encourage all readers to check out the sublime A Hometown in the Heart (1949) not just because it is an exquisite film about the need to be loved, but because Juhn Ahn’s analysis is cognisant of all of the film’s nuances and explores them with great sensitivity. The other film I’d push people toward is Chilsu and Mansu (1988), a kind of buddy picture with Korean stars Ahn Sung-ki and Park Joong-hoon that cuts to the heart of the Korean class system. American Darcy Paquet who provides the chapter on this film has been resident in Seoul for over 25 years and established the always helpful Koreanfilm.org. Paquet offers an insightful look into how this film works and why it is a key document from a time when South Korean society was transitioning from dictatorship to democracy.

If the chapter on Hong Sang-soo’s The Power of Kangwon Province is probably the one that film festival crusaders will turn to first, it also marks the beginning of the second half of the book. Hong’s film and the many films that follow including, Die Bad, Chiwaseon (aka Painting With Fire), 3-iron, My Sassy Girl and The Host are all films that you will have to seek out for yourself. But again, editor Lee has been mindful to make sure that these films are all easily tracked down on DVD (both 3-Iron and The Host were released locally) or on itunes. For the work on more recent South Korean films, David Scott Diffrient’s chapter on the devastating Secret Sunshine (directed by Lee Chang-dong whose film Burning set audiences alight all around the world in 2018) is a must read, and his analysis is enhanced by his informative explanation of how the “kidnapped child” movie became a sub-genre in South Korea.

The one chapter I would find fault with, is the one that many newcomers to South Korean cinema are also likely to turn to. Jeong Seung-hoon’s approach to Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer is the least user-friendly chapter. As I’m not a fan of this film and regard it as the one true dud in Bong Joon-ho’s oeuvre (Give me Memories of Murder — unfortunately not covered in this volume — any day), I wasn’t too upset, but I’d guess that the fanboys who embraced Snowpiercer will be turned off by Jeong’s emphasis on economics, rather than cinema. Personally, I found Jeong’s take on this film, more interesting than the film itself. Regardless, this collection of essays is destined to be a popular text, and will appeal to the (so-called) Asian cinema expert or a novice looking for a way into learning about South Korean films.

Rediscovering Korean Cinema (edited by Lee Sang-joon), University of Michigan, 2019.